James L. Wynn – Experiences as a German Prisoner of War during WWII

SUMMARY:

James Lincoln Wynn (1923 – ) was born in Somerset, Kentucky, and despite being married was drafted out of the Merchant Marine during World War II.

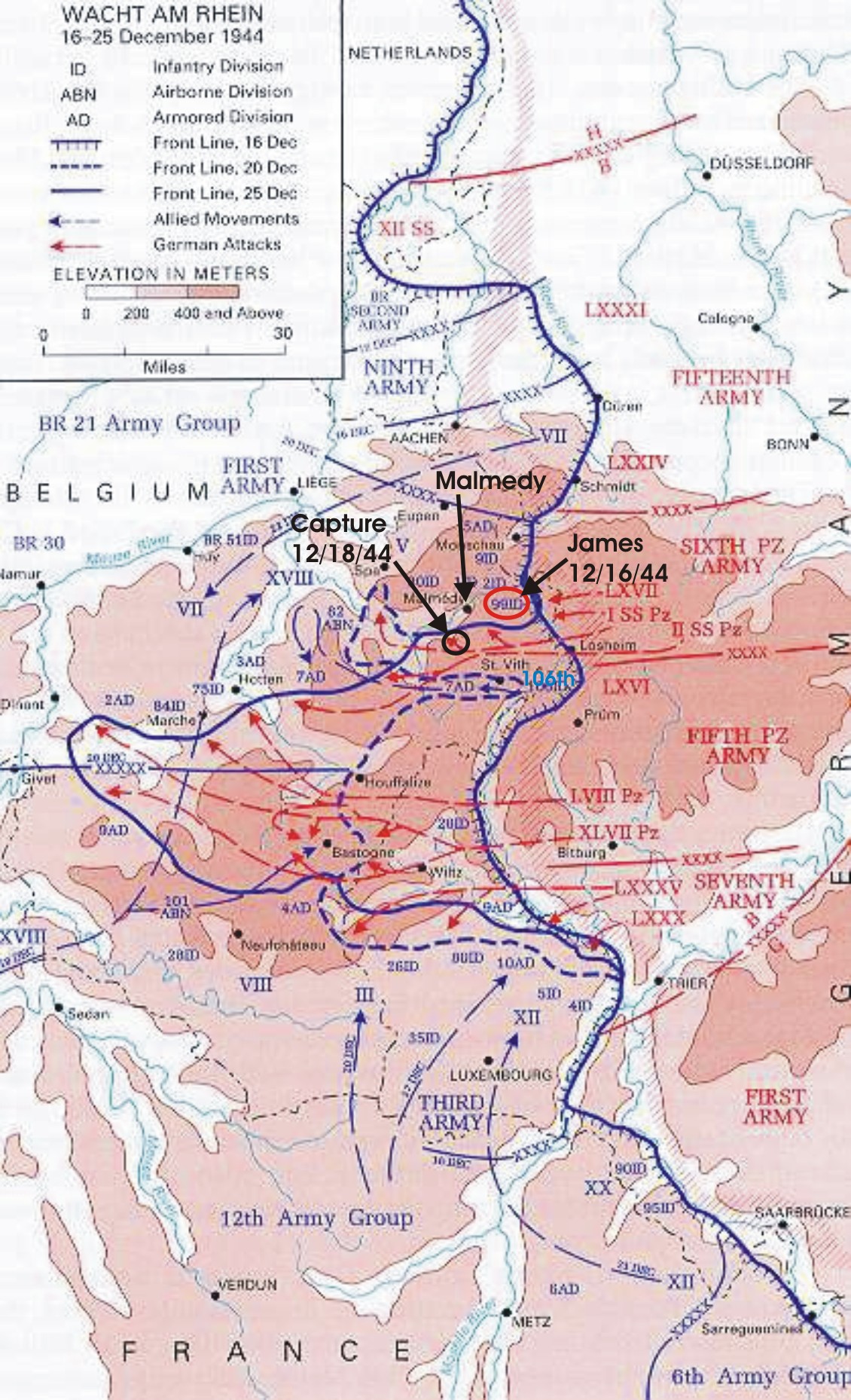

He was captured at the Battle of the Bulge on December 18, 1944, and survived 6 months as a Prisoner of War. He was a personal witness to the horrific Allied bombing of Dresden, Germany. Freed by the advancing Russian Front, then repatriated in late May, 1945, he had lost half his body weight and had not cut his hair or nails, nor had he shaved in six months, because nothing had grown – so deep was his starvation.

Following is his amazing story, with maps and photos.

You will also see a copy of a secret diary James maintained at great personal risk during this experience (below).

SHORT VERSION

In June 1944 the Allies landed in force at Normandy; Patton and his 3rd Army broke out in early July 1944 and began advancing towards Paris. Shortly afterwards, James Wynn landed at Omaha Beach, sent to become a replacement for casualties in the initial assault. He saw his first combat in early September, when he helped capture the port of Brest. By mid-December 1944 he was part of the lead platoon of the US 9th Army that had fought its way to the Ruhr River, the German frontier, when the Battle of the Bulge – the German last-ditch counterstrike – began. After retreating (abandoned by their officers and NCOs), and seeing significant new action at a road intersection, James was taken prisoner; 14 of the 25 men in his platoon were killed during that capture, some just shot in the head as they stood up in their foxholes. Over the next several weeks he was marched and transported by rail to eastern Germany, where he was held initially at prison camp Stalag IVB, then moved to work as a slave laborer at half rations, part of a “komando” in Heidenau, on the southeast side of Dresden near the Elbe River in northern Saxony. He was there when Dresden was fire-bombed (see addendum at the end of this record). Early on in the Allied offensive, James and his buddies had noticed that anyone who became a squad leader lasted a week or two at the most; anyone giving commands became an immediate target of German snipers, so they all refused offers to increase in rank and become squad leaders. This kept them alive, but had serious consequences later on as POWs. They became slave labor, out of sight of the Red Cross, and were even strafed and bombed by Allied aircraft. After losing nearly half his weight from deep starvation (no hair, nails, or beard grew during six months), they moved back west around the time of V-E Day, on the lead edge of the Russian Army and occupation force. They returned to the US Army zone and saw their first American GI’s at Karlsbad (now Karlovy, Czech Republic) on May 15, 1945. James returned to the US on a Navy transport ship, reaching New York harbor on June 11, 1945, and was finally reunited with his wife and mother (read their experience below) on June 18, 1945.

THE FULL NARRATIVE

1. With the Pearl Harbor attack on 7 December 1941, it became very clear that there was going to be a very large war. George Wynn saw the writing on the wall and quickly enlisted. After boot camp, he was sent to Officer Candidate School in Washington State, but after several weeks he and his cohort were suddenly rushed to New York harbor, and shipped to England on the Queen Elizabeth II liner. As a voluntary enlistee he had a choice in what he would be doing, and chose banker/pay-master. George rode out three years of war as a Buck Sergeant (three chevrons) in relative safety in central England (except for occasional German Buzz-Bombs), and took the opportunity to visit every historical site he could find on his days off.

James was married (April 1943), and was serving in the Merchant Marine when he was drafted (he and his wife Alice at that time had no children yet, which would have earned him a deferment). He was inducted on 2 January 1944, and actually stayed longer in Boot Camp than most other recruits in his cohort – he was assigned to take an additional month or so of training as an electrician. Probably for this reason, James missed the Allied assault in Normandy, and arrived after the D-Day (6 June 1944) invasion. He initially departed New York City on July 15, 1944, and reached Edenborough, Scotland, via the same Queen Elizabeth II liner. The QEII at that time had been stripped of all its luxury staterooms, and filled instead on nearly all decks with floor-to-ceiling bunks for the troops, whom it transported across the North Atlantic at such great speed (30 knots) that no U-boat could ever get near it – and destroyer escorts couldn’t even keep up with it.

After landing in Edenborough, Scotland on July 21, James was taken immediately by train to southern England near Yoeville, south of London, where as recruits they received an additional 5 weeks of training on the German weapons they would be facing. They then boarded ships in Portsmouth, and took nets to climb into the landing craft that took them to the huge new floating docks at Omaha Beach on August 31, the site of terrible fighting and casualties in June. From the beach they were marched to high ground and were loaded onto deuce-and-a-half Army trucks. The trucks dropped two men off here, three there, to fill depleted ranks of regiments that had already seen action and suffered casualties.

On September 3, James was the last off the truck as it arrived at Regimental HQ, a farmhouse in open country in western France approximately 30 miles (50 km) east of the port city of Brest. He gave his papers to a First Sergeant, who gave him a box of K-rations around 6 pm and told him to “go out back, dig a foxhole and someone will pick you up in the morning.” He describes digging the foxhole, and settling in for the night all alone, feeling very strange. Around l am a loud BOOM awoke him, but nothing else happened. At 6 am he looked around in the morning light and saw a small crater about 15 feet (5 m) from his foxhole; he speculated it was an anti-tank round fired just to harass them.

JOINING AN ARMY

2. James, at this time, became part of the 9th Army, 2nd Infantry Division, 38th Regiment, 2nd Battalion, Company E, 2nd Platoon. Until then, he didn’t belong to anything – he was just a replacement for someone already killed. Though he finally belonged to something, he and other late-arrivers like him found they were very much not welcome by the battalions they had joined. They reminded them of friends lost. At 8 am on September 8, each man was given extra bandoleers of rifle ammo, four additional hand grenades, and told to be ready to move out at 10:30 am. This was James’ first combat experience: the final move to capture the port city of Brest. On September 18, when the Germans surrendered, James took possession of a German regimental battle flag which he still has today.

When the 2nd Division moved to take their position on the front on September 30, the 2nd battalion of the 38th regiment was chosen by lot to detour to Paris to guard railroad yards and ride shotgun on all supply trains moving to the front. The 2nd battalion rejoined the 2nd Division on the front on November lst. James recalls being deployed in a static holding position covering a 23-mile-long (37 km) section of the Front approximately 20 miles (32 km) east of St. Vith, Belgium.

On or about November 15, 1944, the 2nd Division was replaced by the 106th Division on this section of the frontline – raw new recruits from Indiana. The 2nd Division then moved northeast approximately 15 miles (25 km) to form an attack position on a regimental front between the 9th and 99th Divisions. They marched through the Belgian town of Elsenborn to their new positions to the east. Their offensive began on or about November 23rd. The temperatures at this time were in the (mid-30’s F/0 C) in the daytime and low 20’s (F) at night, with approximately six inches (15 cm) of snow on the ground. Their advance was very slow in a dense forest with large concrete pillboxes spaced approximately 100 to 200 yards (meters) apart, with 100-foot (30 m) fire lanes in all directions so each one could cover and protect the other. There were anti-personnel mines almost everywhere – walking through any forest was extremely dangerous. The fighting was almost continuous from daylight to dark, and daily advances were sometimes no more than 100 yards. They took heavy casualties this entire time, and repeatedly James declined an offer to become a Corporal. He had noticed that Corporals and Sergeants – and especially Second Lieutenants – had a very short life-expectancy.

3. After about 4 weeks of this fighting, they reached their objective: high ground where the forest ended and the open fields of Germany began. They could look to the northeast down at a dam on the Ruhr River about 4 miles (6 km) ahead (probably Hellenthal, Germany). They were on the crest of famous Elsenborn Ridge, the dominant terrain feature in that area. It was now mid-December and there was boot-deep snow everywhere. On the day of the Breakthrough (the Battle of the Bulge began 16 December 1944), they were the lead platoon – the front-line infantry – on the north edge of the breach. They carried M-1 rifles, hand grenades, and field packs loaded with clean socks, K-rations, and ammunition. The Front was moving steadily eastward at this time, the Allied commanders trying to reach the Ruhr River to break into the Rhineland, the German homeland, with all its psychological implications.

On a snowy December 16th, the “Krauts”* broke through to the south of their position – on their right flank. Initially they thought that the new guys on their flank were taking heavy artillery (“having a bad time of it”), but then they got word the next day that the 106th Division to the south had been overrun and obliterated. At 2 pm they got word that they had been out-flanked and even isolated – there were now German army elements behind James’ division. At 4 pm they got the word to “move out” and retreated back westwards. As the lead platoon of the advance at that time, they were naturally “the last dogs out” as James put it. He said he was one of the last three men who walked out 9 miles (15 km) during the night, through an area he described as an unusually eerie, dark forest, floored with snow.

* Krauts, from sauerkraut: the common Allied term for the German enemy at the time. Ironically, James’ mother was Anna Josephine Schneider, born in 1885 in Neu-Ulm, Bavaria, an émigré to the United States with her family in 1886, who spoke only German until she entered elementary school at the age of 7.

James and his buddies knew better than to stray off the narrow path – he said there were mines and trip-wires everywhere. They knew that they were completely exposed to any enemy action that could come against them. About midnight they got to the village where they had started their latest push (Elsenborn, Belgium). The whole division had already moved to high ground to the north, but James’ small platoon was ordered south to guard an intersection. Interestingly, not a single corporal, sergeant, or officer accompanied them: the NCO’s all then scampered off north to where they believed the Allies were regrouping, essentially abandoning these men. James’ group – 25 privates – were armed with only M-l rifles, plus a bazooka team for support. They dug in on the southeast side of the intersection they were sent to, about 50 yards (meters) from the intersection itself. Around midnight they could hear German soldiers – probably lost – walking down the road. They could tell they were Germans by the sounds of their hobnailed boots on the cobbled road. When the Germans heard the order to halt, they ran west toward the intersection – and were shot.

ABANDONMENT – AND CAPTURE

4. As the 18th of December dawned, they could see that they were in an open field. They also realized then that they had been abandoned by their officers and NCO’s. Suddenly two German half-tracks (Probably the Sonderkraftfahrzeug 7/1 – it was armed with a 2 cm Flakvierling 38 quadruple barrel anti-aircraft gun system designed for low-flying aircraft; see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sd.Kfz._7#/media/File:SdKfz_101_KM_m_11_with_2cm_Flak-Vierling_pic3.JPG), opened up on them. Both vehicles had apparently been sitting all night in a brushy field to their immediate north, listening to them arrive and dig in. “Talk about a wake-up call!” said James. No one was hurt because they were still in their foxholes. “30 minutes later we would have been up and eating K-rations,” he said. He added that they had been shot at with .30-cals at least 40 or 50 times by then, “…but the effect was nothing like this.” “Jeff, it was louder than when being strafed by aircraft – each round seemed to explode!” he said. After raking the foxholes for four minutes, the Sd.Kfz 7’s then… just drove away. About 30 minutes later a line of tanks, separated by about 50 yards (meters) each, came up from south to north, and made an eastward turn (“of all things,” James said) at the intersection, right past them. On the backs of each tank there were German troops in white camouflage clothing, and James and his platoon took turns popping up out of their foxholes and emptying their clips at the soldiers. He said they fell off the tanks “like sacks of potatoes.” He and his close buddy George Hazlewood took turns doing this, as they had been trained, and James said he shot the soldiers off at least four or five tanks himself.

Then German infantry appeared advancing towards them from the south. When they came within range, the Americans opened fire and stopped the advance. There was a pause. Then a small reconnaissance vehicle came up and raked their positions with a turret mounted gun – “like a .30-cal machine gun.” A German infantry squad led by an officer with a machine-pistol then walked from foxhole to foxhole and shouted “Raus! Raus mit handen hob!” (Out! Out, with your hands up!) Then James would hear a “BANG!” James told me that he was certain he was about to be killed then, but wasn’t concerned about himself – instead he had a terrible sense that he had failed in his responsibilities to his single mother and his young wife. As he waited for what he thought was inevitable death, he heard a voice “…like me and you talking, Jeff,” that reassured him that THEY would be OK. That HE would be OK. For the rest of his life he had no doubt in his mind about the source of that voice – an angel sent from God. He stood up facing a Shmeisser pistol pointed at his head. He told me in 1968 that he thought the German officer paused then and didn’t shoot him – because he had blond hair and blue eyes.

They followed directions to join other GI’s, already captured. Of the 25 men in his platoon the evening before, only 11 were still alive. It could have been worse: just a few miles farther north, Joachim Pieper’s 12th SS Panzer Division carefully gathered, then cold-bloodedly massacred nearly 500 captured American soldiers – prisoners who had been collected in a field near Malmedy. This group very likely included the officers and NCOs that had abandoned them, because this is the direction they took off for after abandoning the 25 Privates. James said the men who captured them out at the intersection were regular German Army, and not SS; they weren’t trying to rack up a body-count of men they had killed, but were conscript infantry – just like James.

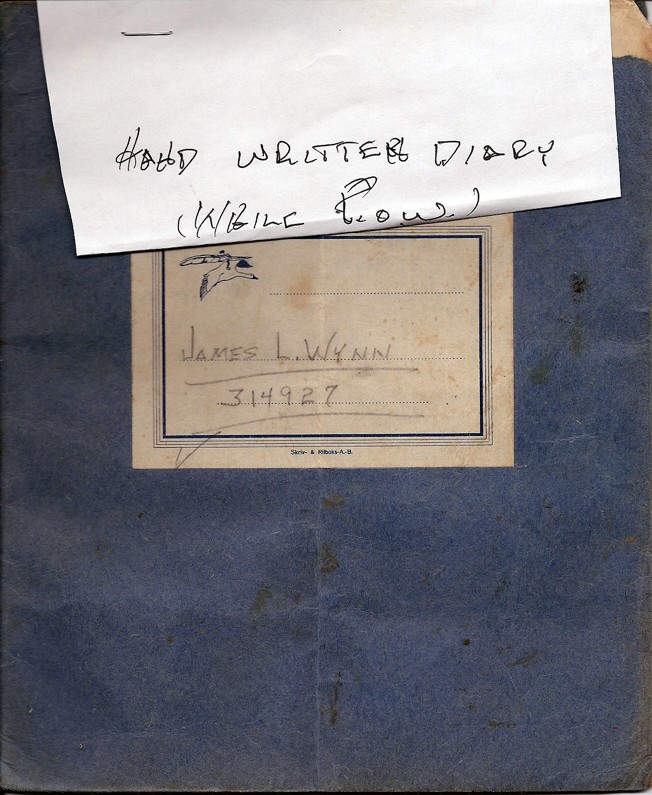

By some miracle, James was able to keep a small soft-side notebook and pencil inside his long-johns during the entire ordeal; it was never discovered by his guards. This diary, which has details and dates, was transcribed by Alice Wynn, and can be seen below and in full near the end of this narrative.

AFTER CAPTURE – THE LONG MARCH

5. After capture on the morning of December 18th, they were accumulated first in a dirt field. American 105-mm Howitzer phosphorus shells began to land around them. They were near a German first-aid station, but it wasn’t clear if Americans were being treated. They were then told to start marching at dusk back down the road the tanks had come from. Their guards were wounded German infantry soldiers. The road had huge numbers of trucks and horse-drawn wagons moving west, bringing supplies to the German troops participating in the Breakthrough campaign. James noticed that the road paralleled a stream, with steep hills on both sides, and he thought they were sitting ducks for any strafing aircraft. This never happened – the Germans had timed the Bulge incursion in part on the weather to give them cover from Allied aircraft.

The POWs ended up about 20 miles (32 km) back from the Front; they were marched at gunpoint all night long to get to the next accumulation point, and were held in what he describes as a huge barn starting on the 19th of December. They were kept there for 3 days, and fed only rotten, golf-ball-sized potatoes, which he said they boiled and that “tasted good,” because they were so hungry. They started marching again, “towards Bonn, Germany” (they saw signs to that effect), and James said that he began to get used to sleeping on concrete floors after 2 nights. They marched 3 days to a camp with 12 buildings, where they arrived on 24 December. The next day, Christmas, the 500 or so prisoners thus far gathered were provided a single 40-gallon (150 litre) large cook pot with sauerkraut and pork pieces – by the time James got his turn, it was just sauerkraut and pork grease – but it was a dinner! That day James saw his first German jet fighter plane. A possible location for this holding camp is between Bonn, and Koblenz to the southeast. At some point early in their forced march James was made to serve on a detail to bury about 30 German war dead.

They were kept in this holding camp for three days. They were then loaded onto a train with wooden cars, red crosses painted on the roofs, and doors tied shut with barbed wire. They were each given a piece of cheese and a piece of bread, and told that this would be all they would get for two days and not to eat it all at once. There were at least 600 Allied POWs by then, packed 40 to a car. They departed on 28 December 1944, and traveled five days and four nights. From a German railway system map, the most likely route started at Koblenz, south of Bonn, and passed through Ehrfurt, around Leipzig, to Muhlberg. Each day the door was opened and a bucket of water was put in for the men to drink – but no food. The train traveled slowly, and often stopped. Each evening at dusk the train would pull into a rail yard and park overnight alongside ammunition or tank cars, disconnect the locomotive and leave until the next morning. The locomotive would then return and start moving again. The nighttime temperature was always in the low 20s (F) and they had to stand and stomp their feet all night long to keep themselves from freezing.

The weather was clear and cold during this train trip. Around 2 pm on 2nd January they stopped to load the locomotive with water. There was a young German soldier manning a machine gun on top of the water tower, and a P-51 flew over. The soldier fired on it, and it flew on. All the POWs marveled at the stupidity of this act, and sure enough, about 20 minutes later the same or another P-51 came back and strafed the entire train. One American was killed and several wounded. Three rounds hit James’ railway car, and one guy took a bullet in his forearm. Since the wounded soldier was near James and his buddy, they started checking him to see how bad his arm was hurt. James had to slit his field jacket arm open to get to the wound. A .50 caliber bullet fell out into the straw on the floor of the railway car. After they had bandaged the man’s arm James gave the bullet to him and said “here is your souvenir.” James saw the guy a week later at Stalag IVB and his arm was in a sling, but he appeared to be all right – and he thanked James for the souvenir which he had in his pocket.

They ended up at a POW camp called Stalag IVB, located about 9miles (13 km) northeast of Muhlberg, Germany (see photo of the entry gate above), and James said he nearly passed out as they staggered off the train. They were issued German prisoner-of-war dog-tags (which James still has; see photo to the right, above section 3) and got their first food: Red Cross ration boxes that they had to share – one box per each five men.

SLAVE LABOR FOR THE REICH

6. Because he wasn’t an officer or a Non-Com, he and other privates were classified for “komando” – labor camp – assignments. They disappeared from Red Cross accounting at this time; they went off the radar: they became slave laborers. There was no Red Cross food, just turnips. James was included in a group of 50 men who were sent by train to a labor “barrack building” (Lager) located in the city of Heidenau, a southern suburb of Dresden on the west bank of the Elbe River. The arrival date was approximately January 22, 1945. He was included in a work gang of 12 men assigned to excavate a deep ditch for a large drain line from a “factory-like” building nearing completion about 3 miles from their Lager. Their already meager rations were cut in half; they realized the German NCO in charge was selling the other half of their meagre food ration on the Black Market, but there was nothing they could do about it. A soldier would march them to the job site at daylight, leave them there, and would come and bring them back at dusk.

They continued on this job until March 13th when Dresden was bombed by B-17 bombers. The city had been bombed by the Brits the night before, but James noted that they didn’t do nearly the damage of the huge B-17’s. Initially he said they watched with interest as huge amounts of material were blasted into the sky… but then noticed that the destruction was approaching them. At the last moment they took cover, and a large bomb fell into the garden of a house approximately 100 feet (30 m) from where they were, across the street watching the progress of the devastation taking place (see section below on the horrific Dresden Bombing). They were then taken in groups of about 10 men on a truck to various locations on the outskirts of the city to repair holes in the highways caused by the bombs. This went on for approximately four days. They were guarded on this particular assignment – not to keep them from escaping, but from being attacked by angry civilians.

At this time the remnants of the original 50 men were moved south 9 miles (15 km) to the town of Pirna, where they were made to unload river barges and reload material onto trucks. James said things went from bad to worse for them, that it was a very grim time. At one point he weighed himself on an industrial scale: 110 lbs (50 kg) counting his uniform, winter field jacket, and boots. He estimates that this meant he weighed just 95 lbs (43 kg). James is nearly six feet tall (180 cm) and normally weighed 185 lbs (85 kg). At least 10 men of the original 50 in the komando did not survive the hard labor and starvation. The group worked in Pirna for approximately 30 days. Near the end, they could hear the Russian Army artillery barrages getting closer by the day.

On or about April 17, 1945, they were marched under guard east across the Elbe River approximately 30 miles (50 km) to a farm in the Black Forest area. On the way to the farm he saw a great fortress on a mountain to their left (east) that they were told held high-ranking Allied officers. This was likely Königstein Castle (POW camp Oflag IVB; Oflag derives from Ofiziers Lager – see photo above). The huge structure dates from the 1200’s, initially built by King Wenceslas to demarcate a boundary between two rival subordinate kingdoms. It was used to hold captured French, American, and British generals in great luxury during both World Wars. Historical records indicate that there was a huge difference in German treatment for officers vs. regular soldiers. The farm James arrived at had a large barn where they joined about 160 other Americans and English POWs.

Historical records indicate that there was a huge difference in German treatment for officers vs. regular soldiers. This farm had a large barn where they joined about 160 other Americans and English POWs. It was here that the camp commander lined them up in front of a machine gun as the Russian Front approached. They were too weak to run, to do anything, and just stood there. The commander took a handkerchief out of his great coat and held it out. This lasted many seconds, then he slowly put it back in his coat and ordered the German soldiers out of the camp. They left, abandoning their prisoners. With nowhere else to go, they stayed and worked for local farmers in exchange for food. Around 7 pm on May 7, while still at the farm, word was sent down from the farmhouse that the war was over.

The next day, two of the former guards who had escorted them to the farm said they would lead the POWs to the American lines located in the town of Pilsen (Czech Republic, but at that time still part of the Sudetenland annexed by Germany in 1938). They started walking immediately in a “very unorganized column” behind the German soldiers, who had discarded their arms. By noon on the 2nd day the German soldiers vanished as Russian forces approached, but they continued on the same highway in a southwesterly direction. On the 3rd day, as they approached the town of Ausig (now Asseco in the Czech Republic), about noon, there appeared a column of Russian trucks loaded with troops led by officers in a command car, who moved into the nearby town to begin their occupation. James said the Russian soldiers were from the Caucasus, were notably short – and by virtue of being there, these guys were very, very tough.

Word was passed up the road by mouth that all of the POWs would have to get off the road, so they moved into the town. James estimated there were now about 300 – 400 POWs gathered. There was a public square in the center of Ausig where the POWs would gather. On the second day a Russian officer advised them that a train would be made up to move them to the American-occupied area the next day. This promise was given daily for approximately four days. Each morning they would get up and go to the square where they would normally “hang out” and always hope this day a train would come.

THE WAR IS OVER, BUT…

- On one morning when James and his buddy George Hazelton arrived at the square, there was no one in sight: they started running to the train depot, which was about 3 city blocks away. When they arrived, there was the train – but it was already fully loaded. Every one of the 10 railway cars was packed with men, and the only space left was on top of the cars. The only alternative to staying was to ride on top of the railway car for the journey. The train left the station very slowly about 2 pm that afternoon and never exceeded 15 mph (25 kph). It traveled all afternoon, all night, and all the next day into the next night, stopping periodically. This was probably the Decin – Ausig/Asseco – Karlsbad/Karlovy rail line still in use today. At about 4 am the following morning (it was still dark), they arrived at Karlsbad (now Karlovy, modern Czech Republic) where the train stopped. Some GIs came down to the train and directed everyone to an area about 6 blocks up the hill. These were the first American GI’s other than their fellow POWs that they had encountered in six months, and it was immeasurably uplifting to see them.

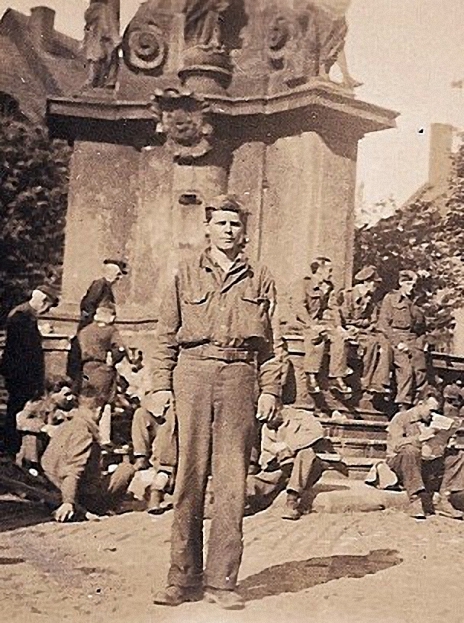

James’ buddy Hazelwood found an unused roll of film on a road, and about two weeks later found a sergeant with a German camera who said it would fit, and borrowed the camera to take some photos. Later he sent some to James, which he still has. Two of these photos are at the top of this document, taken at Loket, modern Czech Republic (verified by Tomas Svoboda, Czech History Association). They were wearing the same clothes they had on when captured at the Battle of the Bulge, and he said they looked pretty ratty. In the photos they look clean-shaven, but had not shaved in six months – no hair nor fingernails grew, so deep was the starvation they suffered. James was exultant as this photo was taken; they were rail-thin and lice-infested, “But we had FOOD!” From Karlsbad they were trucked to Nürnburg. Their clothes were thrown into a big pile here and burned (“lice and all – and boy, those lice could really eat on you,” commented James). They took their first shower here, and were given bars of strong lye-based soap that burned their skin, but he said he felt like a new man. They were issued clean clothes and felt they were GI’s again; they were no longer the “louse-y louts”. They were flown from Nürnburg via C-47 transport planes to Rheims, France, where they were first checked over in a large field hospital, then moved from there to camp “Lucky Strike” at the French port of Le Havre, where they got their first real hot meal: “STEAK!” They spent a week there, then were trucked to the port, where they boarded a Navy troop transport for their return voyage to New York City. James reached New York Harbor on 11 June, and arrived home in Somerset, KY, on 18 June.

They were allowed three months home-leave, then he reported to Camp Oglethorpe in Chattanooga, TN, where he was promoted to Corporal to allow him to serve as a mail clerk until his discharge in January 1946. Though asked repeatedly to re-enlist, he resolutely declined. He didn’t have fond memories of how he had been treated by the Army.

After James returned stateside, he discovered that the Army had lost all his records. He still had his dog-tags (both American and German), but had to submit telegrams sent to his wife to prove to the VA that he had actually served. He had fallen through the cracks. Because he was a POW when what was left of his battalion had received their Citations for fighting in the Bulge campaign, he was lost and forgotten. 57 years later the Army belatedly awarded the Bronze Star to an uncomplaining James Wynn (this was formally awarded in 2001 – the award photo is displayed proudly at the bottom of this page).

THE DRESDEN BOMBING, 13-15 MARCH, 1945

8. “We were being kept as POWs in a Lager in Heidenau on the southeast side of Dresden, digging a big ditch 25 feet deep by 30 feet wide (8 m x 10 m), from a large factory down towards the Elbe River. The Brits had bombed the city the night before, but that was nothing like what the B-17’s would do. About 10 am we heard sirens, and looking west we saw the planes coming. This work area was alongside a two-lane street, cobblestone covered with gravel, and on one side were houses. This road went about 3/4ths of a mile (~ kilometer) down to the Elbe River, and the ditch we were digging paralleled the road. In an open field on one side there were 40 to 50 telephone poles stacked on what looked like low concrete walls. Our guards crawled under these poles and gestured for us to get into the “field office”, which was basically a large wagon with windows from which they had watched us work.

To the north we could see buildings being blown up – huge explosions and debris blasting up into the sky – and it was coming towards us. It was exciting, but we could see that real serious destruction was heading our way, and scrambled to obey the guards’ instructions to get onto the floor of the field office wagon. The bombing stopped only about 400 yards/meters away; it seemed like the B-17s were clearing their 3-bomb “racks” and a 500-pounder (225 kg bomb) hit only 100 feet (30 m) away. Fortunately it hit a garden, where it dug an immense hole. The next day the guards took a work detail of 14 including James to the perimeter of Dresden to fill bomb craters in the roads. It was a good thing they didn’t take them into the city itself, or the people would have killed them, he said. There was a main east-west highway that passed by near their building; it was about 40 feet (12 m) wide. For a day and a half he saw people streaming west on that road, filling it as they walked 10 abreast, “like the living dead, with faces so blackened by soot that they appeared to be West Virginia coal miners coming out of the mine.”

– Wikipedia Commons

PHYSICAL CONSEQUENCES OF JAMES WYNN’S TIME AS A POW

9. For three months part of James’ right foot remained black, but slowly regained its normal color. This was from frostbite. From December 1944 to June 1945 he never cut his hair or fingernails… they didn’t grow during that 6 months. The second photo (top) shows a clean-shaven, skinny young man, but in fact he hadn’t shaved in 6 months. The soles of his feet for the rest of his life have been numb – no sensation – from walking and working for weeks in snow. When he weighed himself on an industrial scale at a factory they were working at in Pirna, he weighed 110 lbs (50 kg) – and this was with boots, clothes, and his winter jacket on. James at the time was 5′ 11″ (180 cm) and normally weighed 180 lbs (85 kg). He told me in 1968 that he had always had problems with his stomach since 1945, which he infers has to do with being fed a tablespoon of potassium permanganate (unsure if accidental or deliberate poisoning while in a POW camp) or from the deep starvation, hard labor at half-rations. I asked James how they communicated with the Germans and the Russians: did anyone speak English? No. Except for a translator at Stalag IVB, everything was done by sign-language, though they knew a few important words like “raus, wasser”, etc.

GEORGE WYNN’S SEARCH FOR HIS BROTHER; WORLD WAR II ENDS

10. From the time of James’ initial capture, George searched for information about his brother. Nothing was known – he was MIA. This went on for many months, and George said he had no idea how his mother, Anna Wynn, and James’ wife Alice dealt with this. He said he used all his poker and banking connections to talk with some “intelligence people”, and finally located people from James’ 38th regiment. These people painted a grim picture, and said that no one had survived from the 2nd battalion – all had been killed. It wasn’t until April 20 that a Red Cross letter from James, sent from Stalag IVB, got to his mother Anna Wynn, and his wife, Alice, letting them know that he had at least survived the Battle of the Bulge.

George was never able to connect with James; they each separately returned to the US. George was on a Liberty ship from England August 4th until August 12th or 13th when they heard over the ship’s radio (conveyed by a drunken ship’s captain) first that a single bomb destroyed an entire Japanese city (Hiroshima, August 6th), then three days later another single bomb had destroyed yet another entire city (Nagasaki, August 9th), and the men on the ship couldn’t get over this: a single bomb! A few days later they heard that the war in the Pacific was over. He told me years later that he had forgotten about his birthday (August 8th) until August 12th or so, when he realized that he was not going to be shipped across the continent to invade the Japanese home islands, where a million casualties were expected. All the men realized that instead they were going home, and would be able to have families. He said that this was the best birthday present he had ever received. I was born in early June 1946 – the very lead wave, the sharp end of the spear of the Baby Boom generation. – Jeff Wynn

ON THE HOME FRONT – by Alice Wynn

11. At home, after James embarked for Europe on July 15th, Alice returned to Somerset, KY, to live with James’ mother Anna Wynn, in her apartment. Alice began working at a local retail ice cream store. When James’ letters stopped after late November, Alice would meet the mailman every day, hoping for some word from James.

On January 19th, Alice received a telegram from the War Department notifying her that James was “Missing in Action” since December 18th. For five months beginning with no word from James, ending with the telegram from the War Department that James was back under Army control, was a stressful time of hope, fear, and no word from anyone. As days and weeks went by, each day became a day of prayer, a deeper realization of helplessness and a greater dependence on the love and protection of God by Alice and James’ mother Anna.

When the mailman became aware of the situation, he promised to check his mail each morning and if a letter arrived, he would call Alice immediately. On April 20th, the mailman called Alice: there was a letter. She immediately ran all the way to the post office for the Red Cross letter James had written while at Stalag IVB on January 10th. This was the only information she received until a telegram from the War Department dated May 28, that James had returned to U.S. military control. James reached New York harbor on June 11, and arrived home on June 18th, 1945.

LOOKING BACK – by James L. Wynn

12. “I accepted the Lord Jesus Christ as my personal Savior and committed my life to Him and to following Him as a born-again Christian believer the first week of January, 1944. I had no idea at that time how soon I would experience what a wonderful and perfect helper the Holy Spirit would be. He helped me maintain a complete trust in His presence and His watchful care, and He gave me a special inner peace that I enjoyed throughout all the experiences mentioned in this very memorable episode of a long and exciting life. At this time in my life, through experiences, considering past events and daily seeking the will of God, I have come to this conclusion: If you seek the will of God and His direction in every decision you make, it will lead you to a true joy in His Presence forever.”

James L. Wynn

Age 99 in 2022

ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL

13. Family portrait of James L. Wynn on his 99th Birthday (23Jan2022) with his five children behind him (from left to right David, Jay, Carolyn, Steve, Jonathan):

~~~~~

14. James L. Wynn just celebrated his 102nd Birthday in Greenville, SC!

To watch an astonishing interview with a Centenarian POW and Survivor of the Battle of the Bulge, click here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9LlTnKXNF6o

I just talked with Uncle James (102 years old @ 23 July 2025). He says he feels better now than in the past five years!

![]()

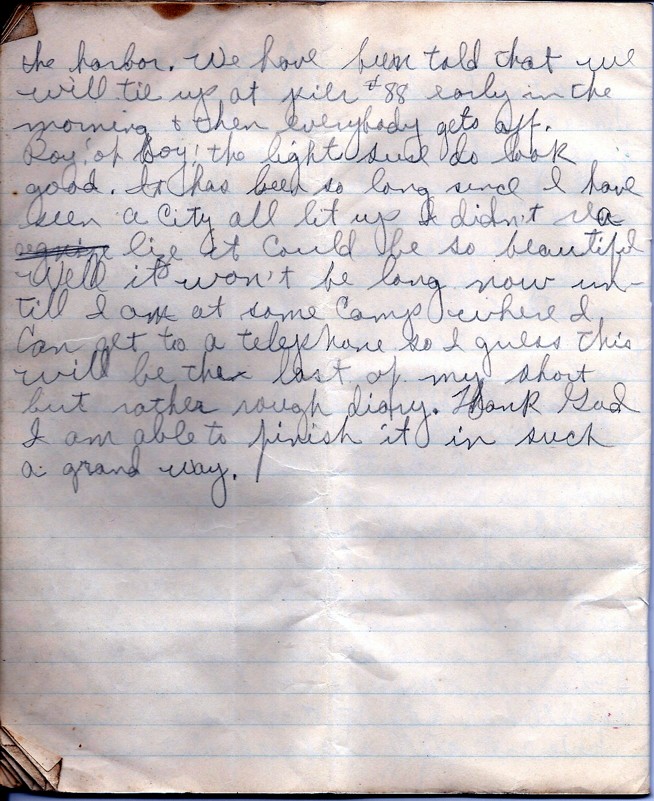

TRANSCRIBED POW DIARY

Diary of Pvt. James L. Wynn (A.S.N. 34917752)

German Prisoner of War Number 314927

“I kept a notebook diary in my long-johns and they never found it.

Of course it was pretty ratty, so Alice typed it up for me.”

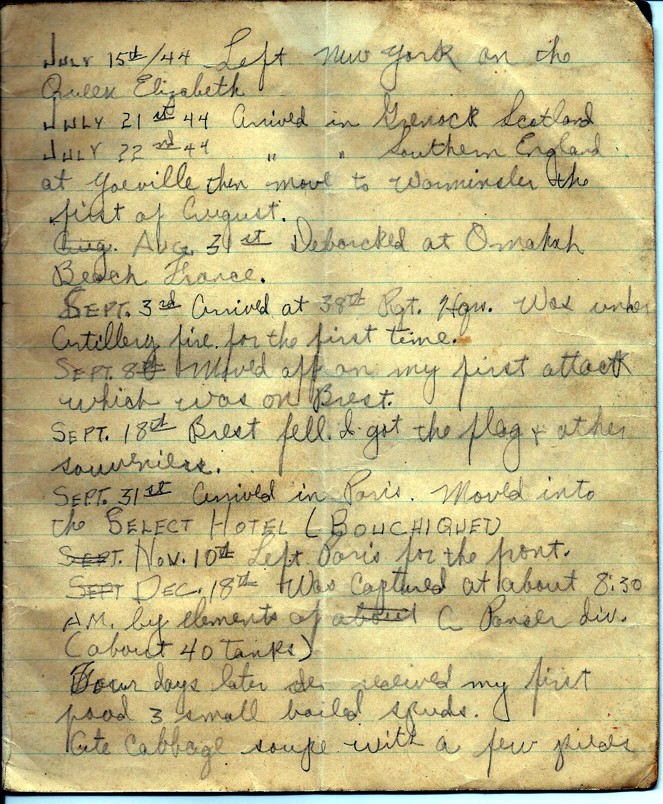

July 15, 1944- Left New York on the Queen Elizabeth.

July 21, 1944- Arrived in Edinboro, Scotland.

July 22, 1944- Arrived in Southern England, at Yoeville, then I moved on to Warminster, August the first.

August 31, 1944- Debarked at Omaha Beach, France.

September 3, 1944- Arrived at 38th Regiment Headquarters and was under artillery fire for the first time.

September 8th, 1944- Moved off on my first attack which was at Brest, France.

September 18th, 1944- Brest fell and I captured a German flag and many other souvenirs.

September 31, 1944- Arrived in Paris, and moved into the select hotel Bouchiqet.

November 1st, 1944- I left Paris for the front.

December 18th, 1944- I was captured by the enemy at about eight thirty A.M. by elements of the Panzer division, about 40 tanks – Four days later I received my first food, three small boiled potatoes.

December 25, 1944- I ate cabbage soup with a few pieces of fat meat floating on top of the water for Christmas dinner, ten kilometers from Bonn.

January 4, 1945- I arrived at prison 4-B at Magdeburg

January 20, 1945- I left 4-B, to go to a work camp.

January 22, 1945- Arrived at Heidenau with forty nine other men to start to work.

January 25, 1945- My birthday- I worked digging a ditch.

March 17th, 1945- I moved to Pirna, and started to work unloading and loading coal and other things.

April 17, 1945- I left Pirna because the fighting was moving in too close.

April 29, 1945- well here I am with approximately 160 other POW’s in a small barn close to the Czechoslovak border about 25 kilometers from Pirna. Jerry has told us that we wi11 be exchanged any day now that the truce has been signed. We are very anxious to get back to our own lines, because we are slowly starving here. We have been living on approximately three medium sized potatoes and

250 grams of bread, now for four days. We received 150 grams of sugar last night, and it was the first I had tasted for a long time.

I sure will be glad to get some new clean clothes again, the clothes I have now are dirty and the body lice are about to eat me up.

They told us we have about 50 or 60 kilometers to march and some of the boys probably won’t make it because they are too weak.

May 7, 1945- well we are still here at the barn, and we found out for certain that the war is over, but it is still going full blast and Russian artillery is getting very near.

May 8, 1945- We moved out this morning at four o’clock, and it is now almost six P.M. with about three kilometers to go. That will make almost forty kilometers we have walked today, on 250 grams of bread, two spoonfuls of meat, and some boiled potatoes and a little bit of sugar. We are trying to get to our lines but we may run into

the Russians first.

May 9, 1945-Arrived at 5 A.M. Have been walking twenty four hours now. It is after 7 A.M. and I am very well filled up on butter, meat, honey, etc. obtained from trucks strafed by Russian fighters. I have eaten better this morning than I ever did since I have been a prisoner of war. They just said our boys would be here in an hour. I hope it is true. It is now late in the evening and the Russians have come through.

May 10, 1945- It is now 9:30 A.M. and I have just completed a good night’s rest and I feel much better. I hope we leave today for our Lines.

May 11, 1945- Well it is now 7:00 P.M. and another day has passed and we still haven’t heard when we are to leave. My buddies and I are staying with a Czechoslovak civilian family in part to protect them. We are still getting plenty to eat and getting along just fine, but I want to get started home soon because I know you are worrying about me, but I know it won’t be long now. The Russians are treating us just fine but I hope an American officer gets things organized soon.

May 12, 1945- It seems we missed a train late this evening but there should be another one tomorrow.

May 13, 1945- It is now 11:30 A.M. a beautiful Sunday morning and I am on a train waiting to pull out for a point 180 kilometers from here. I am writing this sitting on top of a box car. “I AM On My Way.”

It is now 12:30 and we are moving along slowly and everyone is very happy, and all the civilians are waving and shouting at us as we go by.

May 14, 1945- 12:00 o’clock noon. Well I am still on top of a box car and the train has stopped all morning for some reason. We are somewhere near Karlsbad. If the train moves at all today, I hope to see our boys because we are getting closer to where they are supposed to be.

May 15, 1945- It is now almost 2:00 A.M. and I just finished my first C ration in about six months. They (GI’s) unloaded us off the train about Midnight and brought us here in this building in Karlsbad and fed us.

I also saw my first American soldier a few hours ago. I sure feel good.

May 15, 1945- Midnight. Well I am now in Neuenburg Germany. We were brought here to an airfield from Karlsbad by truck. I sure have seen some pretty country and am now well on my way home. I am feeling much better now, too.

May 16, 1945- It is now twenty minutes past noon and twenty seven of us are waiting to get on a plane and fly to Reims, France. We started out in a plane about an hour ago and it blew out a tire so now we are waiting on another one. It is now ten minutes until two and I am in a C-47 on my way to Reims, France. We have just taken off.

4:10 P.M.- Just arrived at Reims France.

7:30 P.M.- Well I feel much better now that I have had a good hot shower got a new set of clothing from socks to cap and just finished my first G.I. meal of turkey, corn, lima beans, peaches, and my first white Bread and butter in five months. I am waiting to leave for Le Havre to get on a boat. I wish I could send you a wire, but I can’t.

May l7, 1945- It is now 2:45 A.M. and I am on a hospital train bound for Le Havre.

8:30 A.M.- Just finished breakfast (in bed). Even when I was in Germany starving, I never knew white bread could taste so good. It tastes better to me now than any kind of cake or pie did before I was a prisoner.

10:00 P.M.- Just arrived at a big camp about five miles from Le Havre.

May 18,1945- It is now 10:00 A.M. and I have had breakfast and have written to you and Mom. It seems I will be here for about a week and then leave for the states. I tasted my first fresh eggs this morning in about six months.

12:00 Noon- Just returned from the Red Gross tent where I sent you a cablegram to let you know I have been liberated. You are supposed to get it in 56 hours.

May 22, 1945- Still at camp “Lucky Strike” about 40 miles from Le Havre.

3:00 P.M. Just saw Eisenhower. I was over at the Red Cross tent and he drove up with some other big shots, got out of his jeep and moved on up through us asking questions and cracking jokes. He stopped and talked to one of my buddies a long time.

June 5, 1945 – Well it is now about four P.M. and I am well on my way out in the old Atlantic on my way home. I was sick most of the day yesterday and this morning, but I have been feeling better this evening. The boat I am on t s a navy transport. I tasted my first fresh bananas yesterday morning in over a year. They sure tested good. I also ate my first orange in about six months too, here on the boat. Now that I am practically back home, the whole world looks brighter, just like a very sweet dream coming true, and as usual I have God to thank for making it all possible. He has watched over me continuously now for many months. Without His help I would have lost faith many times, when the days were as black as the nights and an empty stomach continuously turned my thoughts to food. I have lost time in studying and my work I want to do, but I have learned that God has blessed my country with gifts too numerous to mention, that Does not exist anywhere else.

June 9,1945- It is late in the evening and I have just finished Supper and come out on deck for some fresh air before turning in. Well they say we will dock tomorrow night, so I guess this will be my last Saturday night outside the states for awhile. I hope it is my last forever. We sure have been fed good on this boat, two

hot meals a day and a K ration for supper. It is so much better than we were fed on those English boats. The sky is rather cloudy and it doesn’t look like we will have a very pretty sunset. I have been sick only one day so I guess I am lucky because the water has been rather rough all the way.

June 11, 1945- Well it is now 10:30 P.M. and we are in New York harbor. We pulled in about 7:00 this evening. We are still anchored out in the harbor. We have been told that we will tie up at pier #88 early in the morning and then everyone gets off. Boy! Oh Boy! the lights sure do look good. It has been a long time since I last saw a city all lit up, and I didn’t realize it could be so beautiful.

Well it won’t be long now until I am at some camp where I can get to a telephone, so I guess this will be the last of my short, but rather rough diary. Thank God I am able to finish it in such a way.”

NOTE: James reached home on June 18, 1945.

![]()